The Tenderness and Rawness of Fasting

After two months of house worship and empty church buildings, the Synod office of GMIT (the Evangelical Protestant Church of Timor) encouraged households to observe a day of fasting, an uncommon practice among GMIT’s rich tradition of rituals.

The fast, right after Ascension Day, was to prepare congregants for pencurahan or the outpouring of the Holy Spirit. This is a time when the early Christians, cognizant that the Spirit of Christ had never left them, renewed their commitment to and participation in the mission that Jesus began.

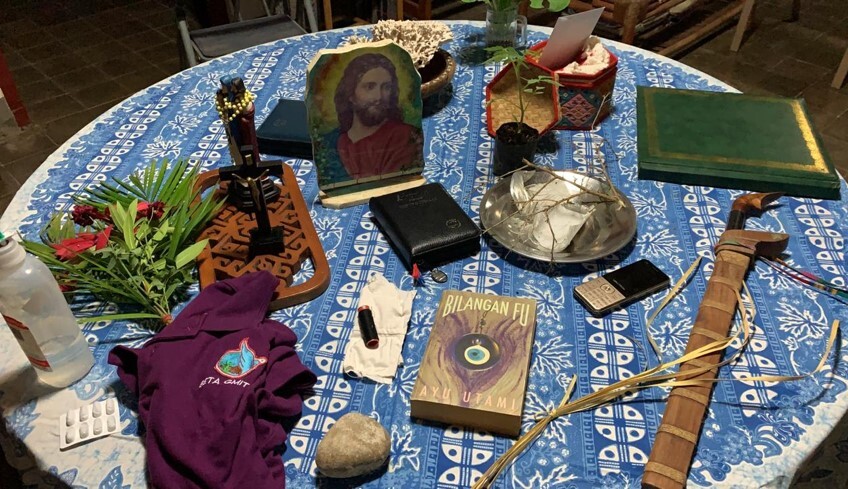

Guidelines for the fast included 12 topics related to COVID-19 for prayers at the beginning of each hour. In our household, we divided up the topics and the three children with us took turns hitting a gong as our “call to prayer”, not unlike many GMIT church custodians, pre-COVID, hit empty bomb shells from WWII as a call to Sunday worship. The person leading the hourly prayer brought something to the table that symbolized her or his prayer. For me the day was marked by tender reflections and interesting objects that became a source of welcome anticipation.

7 am: a shattered jar and dead branch symbolized a prayer seeking the forgiveness of sins—how we hurt each other, damage the earth, and oppose God’s will;

7 am: a shattered jar and dead branch symbolized a prayer seeking the forgiveness of sins—how we hurt each other, damage the earth, and oppose God’s will;

8 am: a bamboo-sheathed kelewang (a ceremonial sword) symbolized a prayer for governments around the world that they, as the only institutions recognized to have authority for the legitimate use of force, use their authority wisely;

9 am: a prayer for all those being treated in hospitals was represented by a stone for the burden they carry and a Bible as the way to lighten this burden;

10 am: a prayer for those in quarantine was represented by things they can do—patching (needle and thread), reading (a book, a Bible), or weaving a basket (a dried palm frond);

11 am: funeral symbols in the form of a bouquet of palm fronds and flowers, and a small cross introduced a prayer of comfort for family members grieving those who have died;

12 pm: prayers for medical personnel treating infected patients began with a joint “thumbs-up”, symbolic hugs of gratitude, and singing “I Must Have the Savior With Me”;

1 pm: a small bottle of medicine accompanied the prayer for a vaccine;

2 pm: some young bok choy from our garden opened a prayer of hope that all those suffering the social-economic impacts be able to grow gardens or have access to them;

3 pm: a shirt bearing the logo of GMIT’s most recent quadrennial assembly that features a dove of hope with an olive branch in its beak was the symbol for a prayer for GMIT;

4 pm: a prayer for families (dealing with children’s education, observing medical protocols, facing fears, etc.) began with showing some pages from a family photo album;

5 pm: 11-year old Santi began her prayer for all people sick with other illnesses with a half-filled bottle of saline solution, some pills, and a cellphone as a means of giving them comfort;

6 pm: a tomato plant seedling symbolized a prayer for the earth and for repentance of our failure to protect God’s blessing of creation.

The day felt like a fuzzy family hug; my soul basked in our commitment to deepen our spiritual life together. Yet two incidents reminded me that smug piety is a temptation, for our joint fasting and hourly prayers evoked not only tenderness and sharing, but also rawness of emotion and the surfacing of tensions. Between two afternoon prayers, I sought out John who was watering the garden to bemoan yet another indication of our provincial government’s mixed, and therefore, confusing messages about COVID-19 (sound familiar?). While chatting, a small tomato—very red—beckoned to me. I plucked it from the vine and popped it in my mouth. I did it again. Having finished my chat with John, I returned to work at my desk. About 30 minutes later, as I worried a tomato seed between my teeth, I suddenly became aware of my mouth, remembered the tomatoes, and was devastated. I had fallen asleep on my fast watch: “Could you not stay awake with me one hour?” It took me awhile to recover as I was ashamed to admit I lacked the stamina of vigilance needed for the spiritual renewal I was boasting about to myself. The second incident was the morning following the fast: an audibly disturbing spate between two of the adults sheltering with us. Given the circumstances, and their history of unconfessed and unresolved tensions, I suppose it was inevitable, but gratefully John’s “shuttle diplomacy” seemed to work as by suppertime the tension had passed and a sense of harmony restored (the “air” conveyed it).

Our household continues to pray together, through rawness and gratitude, for the life we have been given and through which we continue to seek new ways to participate in the mission we have also been given. We think of you too, in the missions to which you are committed. May we join together, connect with each other as best we can, so that we can better move towards an uncertain future with hope and love.

Karen Campbell-Nelson serves with the Evangelical Christian Church of West Timor in Indonesia. Her appointment is made possible by your gifts to Disciples Mission Fund, Our Church’s Wider Mission, OGHS and your special gifts.