Ascension and Pentecost, 2019

After a lifetime spent in either the Northern Hemisphere or the tropics it seems a little odd to be commemorating Ascension Day and Pentecost as temperatures are getting cold. (And even if winter isn’t technically quite here yet in Lesotho, nor in its full fury, things have definitely shifted from cool to cold; most conversations pretty quickly include the phrase “Hoa bata,” (it’s cold) and the acknowledgment that winter is here.)

Yet honestly this seems right to me, certainly for the Ascension. That is, the Ascension, as told in Acts, has always had a certain chilling edge to it, especially when viewed from the standpoint of Jesus’ followers: the loss of a leader and dear friend after seemingly having just regained that leader and friend; the end of a wondrous, life-changing era; the shift of responsibility to those who clearly do not seem ready for it. I’ve never felt the supposedly triumphant element that others do on this occasion, and I’m glad the weather seems to be in agreement here. The colder weather and loss of daylight somehow felt right on that holiday—and it is a holiday in Lesotho—with the sun not willing to rise out of the northern sky, the faithful masses heading to worship services early on a Thursday, and the stores and businesses in the city unsure if they should be open or closed.

Yet honestly this seems right to me, certainly for the Ascension. That is, the Ascension, as told in Acts, has always had a certain chilling edge to it, especially when viewed from the standpoint of Jesus’ followers: the loss of a leader and dear friend after seemingly having just regained that leader and friend; the end of a wondrous, life-changing era; the shift of responsibility to those who clearly do not seem ready for it. I’ve never felt the supposedly triumphant element that others do on this occasion, and I’m glad the weather seems to be in agreement here. The colder weather and loss of daylight somehow felt right on that holiday—and it is a holiday in Lesotho—with the sun not willing to rise out of the northern sky, the faithful masses heading to worship services early on a Thursday, and the stores and businesses in the city unsure if they should be open or closed.

But Pentecost feels a different matter. Isn’t this the story where tongues of fire, individual flames, are alighting on Jesus’ followers? Shouldn’t that be a day where the radiant warmth of spring helps to guide the story? Well it may feel that way for those of us who are used to it, but there’s no reason it needs to be. After all, the warmth of fire is no less meaningful in the cold, and the light of a flame no less valued in days of little daylight. (In fact, a pretty good argument could be made that it is much more important then, as anyone who has ever been in a Northern Hemisphere church on Christmas Eve has undoubtedly heard.) Pentecost is about the fire from within, not from without.

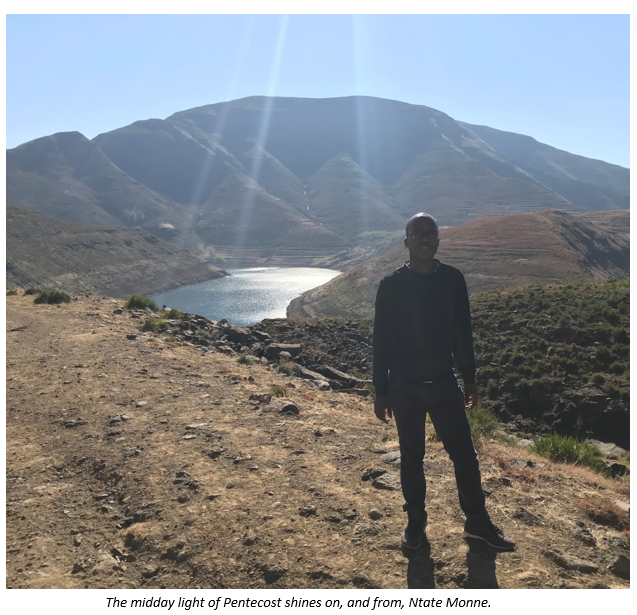

I found this to be true as I traveled on a cold Pentecost morning with Ntate Monne. Ntate Monne (and Ntate is a title, loosely meaning sir) is the Principal Agent for the construction project of a new church and pastor’s house at Molika-Liko Parish. This mountain parish in the middle of the country lost its church building years ago with the construction of Mohale Dam. Saying this region is beautiful is an understatement. Saying it is difficult for a community to lose and not have a church building for years is also an understatement. But in March our partner denomination, the Lesotho Evangelical Church in Southern Africa, was able to start construction on this new church hall and pastor’s house. Ntate Monne is responsible for monitoring the progress of this work, and I have joined him on a few such trips to inspect the work, and I always enjoy his company.

I found this to be true as I traveled on a cold Pentecost morning with Ntate Monne. Ntate Monne (and Ntate is a title, loosely meaning sir) is the Principal Agent for the construction project of a new church and pastor’s house at Molika-Liko Parish. This mountain parish in the middle of the country lost its church building years ago with the construction of Mohale Dam. Saying this region is beautiful is an understatement. Saying it is difficult for a community to lose and not have a church building for years is also an understatement. But in March our partner denomination, the Lesotho Evangelical Church in Southern Africa, was able to start construction on this new church hall and pastor’s house. Ntate Monne is responsible for monitoring the progress of this work, and I have joined him on a few such trips to inspect the work, and I always enjoy his company.

In many ways there was nothing different about Ntate Monne on this most recent trip, as he was his usual friendly, talkative self. Schooled as an architect, and a very good softball/baseball player on the side (playing, in fact, for Lesotho’s national teams, in a country where those are not the principal sports), Ntate Monne has a wide-range of interests that come up in conversation—from life lessons learned on the diamond, to his opinions about a number of the building we drive by, to stories of his young son, to thoughts on the current political situation in Lesotho, to his desire to return to school to get his Masters in Architecture (and the difficulty in doing so), to any number of other areas, really.

But the moment on this trip when I sensed the spirit of Pentecost was when he talked of something he often mentions: his desire to do something positive here in Lesotho. He was listing all the things Lesotho has going for it—water, natural beauty, potential tourism, mineral resources, friendly people, unique customs, abundant wool and mohair, just to name a few—when he kept coming back to how he hopes to find a way to bring such disparate things together in order to benefit everyone, especially those left out. He just wasn’t sure how. Sometimes he talks of wanting to have a space where youth could learn softball and baseball as well as life skills, but this was something even more than that, a more comprehensive longing. This was about a hope for all here, and by extension love for all everywhere. He’s hardly the only person to think about such things, which is precisely why this was the spirit, or Spirit, of Pentecost at work. Pentecost isn’t about a singular flame in winter bringing comfort to our lives, like we hear with Christmas; rather it’s about many flames in many lives which, when put together, demand we change the way we live. Theologically Pentecost is the far more revolutionary day, as it is the most theologically revolutionary day of the church year. If we don’t recognize it as such it is because it often doesn’t look like the uncontrollable blaze we expect it to be, but rather looks like the glow of the lives of people like Ntate Monne. Though he’s hardly the only person here we’ve felt that warmth from, I for one was grateful to experience that flame, that Spirit, not in the warmth of spring, but in the coldest time of the year. Somehow it seemed just a little bit brighter because of it.

But the moment on this trip when I sensed the spirit of Pentecost was when he talked of something he often mentions: his desire to do something positive here in Lesotho. He was listing all the things Lesotho has going for it—water, natural beauty, potential tourism, mineral resources, friendly people, unique customs, abundant wool and mohair, just to name a few—when he kept coming back to how he hopes to find a way to bring such disparate things together in order to benefit everyone, especially those left out. He just wasn’t sure how. Sometimes he talks of wanting to have a space where youth could learn softball and baseball as well as life skills, but this was something even more than that, a more comprehensive longing. This was about a hope for all here, and by extension love for all everywhere. He’s hardly the only person to think about such things, which is precisely why this was the spirit, or Spirit, of Pentecost at work. Pentecost isn’t about a singular flame in winter bringing comfort to our lives, like we hear with Christmas; rather it’s about many flames in many lives which, when put together, demand we change the way we live. Theologically Pentecost is the far more revolutionary day, as it is the most theologically revolutionary day of the church year. If we don’t recognize it as such it is because it often doesn’t look like the uncontrollable blaze we expect it to be, but rather looks like the glow of the lives of people like Ntate Monne. Though he’s hardly the only person here we’ve felt that warmth from, I for one was grateful to experience that flame, that Spirit, not in the warmth of spring, but in the coldest time of the year. Somehow it seemed just a little bit brighter because of it.

Mark Knowles serves with the Lesotho Evangelical Church. His appointment is made possible by your gifts to Disciples Mission Fund, Our Church’s Wider Mission, and your special gifts.