The Mass of the (Amazonian) World

Written by: Alex Maldonado-Lizardi and Xiomara Cintron-Garcia who serve with the Christian Centre for Justice, Peace and Nonviolent Action (Justapaz), Bogota, Colombia

To pronounce God’s name is

to affirm the possibility of open paths,

it is to bet on the unpredictable,

even when what we expected

no longer has the conditions to come to fruition.

-Ivone Gebara

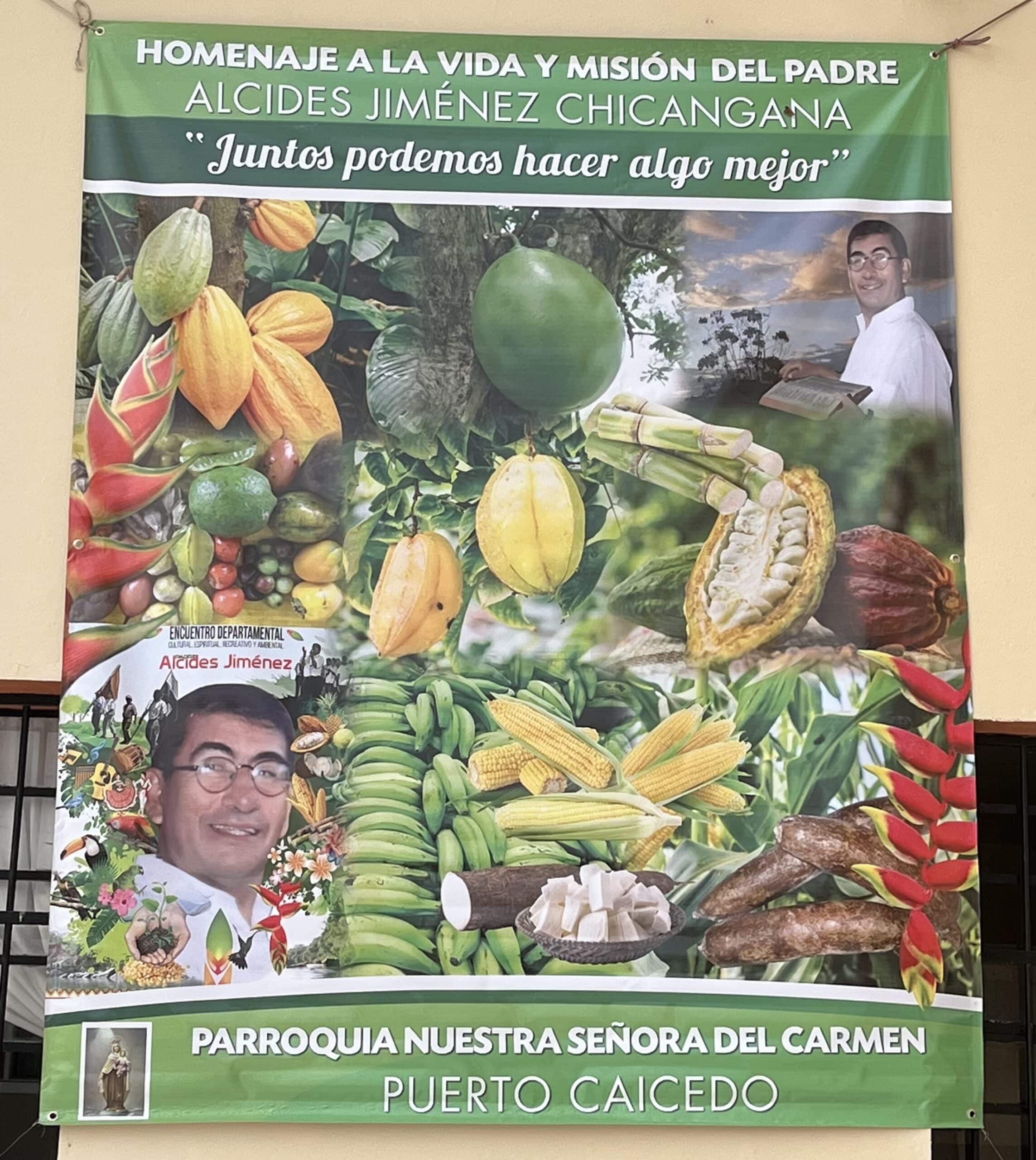

Outside the Our Lady of Carmen Parish, right at 9:00 a.m., there are already tents and tables with hot “aborrajados”[1], pumpkin cupcakes, açaí and hibiscus flower juices, coffee, and buckets of cold oatmeal. It’s a huge square plaza that every September 11th hosts the “Departmental Cultural, Spiritual, and Environmental Celebration for Father Alcides Jiménez.” By this time in the morning, the stews for lunch are already cooking in the square, farmers cross it with their products, and the UN trucks are still warm from the 3-hour drive from Puerto Asís to Puerto Caicedo, Putumayo.

Professor Edilberto and I sat on a bench, share a cupcake and coffee, and he tells me about the pumpkin crops and sapote trees in Puerto Caicedo, but also about Father Alcides, who died at the foot of one of them.

He told me that Father Alcides wasn’t a 19th-century chronicler nor an expedition captain; he wasn’t a naturalist scientist like Von Humboldt, nor an encyclopedist, an apostolic prefect, or missionary conqueror of the colonial settlements along the Putumayo River.

Instead, he told me that Father Alcides Jiménez Chicangana officiated mass in the midst of the Putumayo Amazon surrounded by farmers and parishioners, jasmine bushes, annatto, ferns, and heliconias. He also tells me how he organized the local farmers to develop “integrated farms as an alternative to coca cultivation,” since the state’s alternative was different: to destroy half of the coca bushes in the region with glyphosate[2]. Father Alcides said the best thing was to “plant food, give health, and provide organizational development.”[3] According to the Commission for the Clarification of the Truth, in his pastoral and organizational work, Father Alcides focused on five fundamental “seeds” for the community’s “good living” (sumak kawsay): disease prevention, vegetable garden development, economy, participation and autonomy, and the policy of community participation[4]. “The future of human life is self-sufficiency!” he would proclaim.

He insisted on the conservation of native seeds, rejection of GMOs, strengthening of agricultural production, promoting hygiene, and transforming the fruits of the land. He supported the formation of community cooperatives and rural community promoters who traveled the pathways of the territory to verify the progress of sanitary unit projects, kitchen improvements, crops, and processes for transforming Amazonian fruits into cakes, jams, cookies, and medicinal products made from the leaves, stems, roots, and fruits of regional plants—all of these as alternatives to the disasters of coca monoculture, drug trafficking, and violence.

With the blossoming of these processes, a need for communications arose. For this reason, and under the benefit of a call from the National Government, Father Alcides supported the project that would later be known as “Ocaina Estéreo Community Radio.”

The 14 years of priesthood and service to his people are captured in one of his speeches: “It is not enough to live in a community to be part of it; you have to feel its problems and be active in their solution.”

On September 11, 1998, at noon, two men in white ponchos entered the church of Our Lady of Carmen Parish and ended Father Alcides’ life while he was celebrating the Eucharist. His body rests under the shade and breeze of a sapote tree next to the church.

What does the gospel walk of such a person do to our lives, to the territory, to the fatality that sometimes holds things together?

The commemoration began at 10:00 a.m. in the church with the participation of several priests from Putumayo, municipal government staff, students, and people in general. During the meeting, Father Alcides’ sister, Olga, who had come from the city of Popayán, Cauca, shared a short reflection:

It’s incredible… those who silenced your voice were going to destroy what you had built, but they didn’t count on the fact that Alcides is the people, their land, their harvest, and their voice; that he still feels like a son of God. They didn’t silence his voice; it is felt with greater strength in the very land he walked on. Those who killed him were wrong because the wind and the trees pronounce his name, and his teachings continue to accompany us.

In his homily, around the sermon on the plain in the Gospel of Luke, and from the same altar where Alcides had been shot, Father Campo Elías de la Cruz spoke of actions driven by love. He pointed to the God of the great homeland, encouraging us to hope because “with utopia, there is a path. To remember Father Alcides is to think about that path which, for him, beyond utopia, is sustained by the people.” He invited everyone to live an Amazonian-faced church by updating Father Alcides’ legacies. In this way of walking, the Beatitudes are not foreign to the realities of the territory: they accompany the lament where the poor nourish the Beatitudes and are positioned as a condition for the joyfulness and grace of life. In that gesture, Father Alcides was able to say to a woman who was crying, “Woman, let me cry with you,” making the pain of the other alive, and the Beatitude alive.

Walking with the poor becomes one with the pain of the Amazon. There are no departmentalized pains. The pain of the poor is the pain of the land; the pain of the land is the pain of the poor, and the poor are blessed. There is no care for creation if there is no deep living of what is created. “Isn’t this our problem?” asks Campo. “If it doesn’t hurt us, what will happen to the poor?”

He challenged us with more questions: “What does the martyrdom of Father Alcides tell us? How long does his spirit remain? Who has changed his deep message for a caricature?” He asked these questions knowing that “the rich have already had their comfort since they have taken ‘easier’ paths,” and that, on the contrary, “whoever loves their neighbor does not accumulate the unnecessary because it might be necessary to someone else.”

Then, he gave an alternative pastoral example from the very community that was listening that morning:

You decided not to plant coca and chose other seeds. The day we run out of seeds, we will die. The day we run out of water, we will die. The presence of God is in the Amazon. We embrace these alternatives when we embrace the land, the Amazon, “the fraternity of the leaves”… And while the multinationals are draining the life out of the territory, it is important to look with God’s eyes at what is happening to the world. The rich, the companies, the corporations… will have money, but no food, no seed. This is how we must stubbornly believe in the dream of Jesus of Nazareth. Our biggest tree is to believe, to promote harmony, food, and seed. To live the cosmic Eucharist.

At the end of the service, Edilberto told me that one day in August 2022, Father Campo found a small, tattered book with green covers tangled in fluff and trash in the parish. It was an old edition of Teilhard de Chardin’s Hymn of the Universe where an urgent message appeared: Community life in tune with the gospel awaits on the union and solidarity of all creatures that are consecrated in the World, since all are suspended from the same real center, a true life we experience in common. The opposite of this is the blind effort to feed on a single reading of reality, a “monodiscourse” that requires the support of violence to sustain itself on a world that it destroys[5].

Father Alcídes, during a Eucharist celebrated at the altars of the jungle, told the farmers of the territory:

Today, Jesus Christ arrives at this mountain as he liked, and he mixes with us and walks here and gathers us so we can share the “yotas”[6], the “chicha”[7], the “guarapo”[8], the friendship, some sweets, a “sancochito” (stew). Good Father, send your spirit over this Mass, which is the Mass of nature and of us[9].

This is the cosmic Eucharist over the Amazonian earth, a way of knowing how to pronounce God’s name on the open path and the fresh land.

Amen.

[1] “Aborrajados de plátano maduro” or “Aborrajados colombianos” is a dish of deep fried plantains stuffed with cheese, sometimes also guava or “chicharrón” (fried pork belly) in Colombian cuisine.

[2] https://kaired.org.co/wp-content/uploads/Alcides-Jimenez-Chicangana.pdf

[3] https://kaired.org.co/wp-content/uploads/Alcides-Jimenez-Chicangana.pdf

[4] https://www.comisiondelaverdad.co/las-semillas-del-padre-alcides

[5] Taken and adapted from the book Incidencia del pensamiento Cósmico del jesuita y paleontólogo Teilhard de Chardin SJ (1881 – 1995) en el pensamiento Andino – Amazónico del Padre Alcides, by Ediberto Lasso Cárdenas, September 11, 2023.

[6] Also known as Chayote.

[7] A fermented, typically alcoholic beverage of Latin America, emerging from the Andes and Amazonia regions made from a variety of maize landraces.

[8] Sugarcane mostly fermented juice.

[9] Taken from the book Incidencia del pensamiento Cósmico del jesuita y paleontólogo Teilhard de Chardin SJ (1881 – 1995) en el pensamiento Andino – Amazónico del Padre Alcides, by Ediberto Lasso Cárdenas, September 11, 2023.

Decir Dios es afirmar la posibilidad de caminos

abiertos, es apostar a lo imprevisible

aun cuando lo que esperábamos

ya no tenga condiciones de realizarse.

-Ivone Gebara

La misa sobre el mundo (amazónico)

Afuera de la Parroquia Nuestra Señora del Carmen, apenas a las 9:00 am, ya hay carpas y mesas con aborrajados calientes, ponqués de zapallo, jugos de açaí y flor de Jamaica, café y baldes con avena fría. Es una plazoleta enorme la que cada 11 de septiembre aloja el “Encuentro Departamental Cultural, Espiritual y Ambiental, Alcides Jiménez”. A esta hora ya huelen los guisos para el almuerzo sobre la plazoleta, los campesinos la cruzan con sus productos y las camionetas de la ONU aun tienen los motores tibios del recorrido de 3hrs de Puerto Asís a Puerto Caicedo en el departamento del Putumayo.

El profe Edilberto y yo nos sentamos en una banqueta, compartimos un ponqué y un café, y me habló de los cultivos de zapallos y los árboles de zapote en Puerto Caicedo, pero también del Padre Alcides, que había muerto a la raíz de uno de ellos.

Me contó que el Padre Alcides no era un cronista decimonónico ni capitán de expedición; que no era científico naturalista a lo Von Humboldt ni enciclopedista, prefecto apostólico o misionero conquistador de los caseríos junto al río Putumayo.

Me cuenta, más bien, que el Padre Alcides Jiménez Chicangana oficiaba misas en medio de la amazonía del Putumayo rodeado por campesinos y feligreses, arbustos de jazmín, achiote, helechos y heliconias. También cuenta cómo fue organizando al campesinado del territorio hacia el desarrollo de “granjas integrales como alternativa al cultivo de coca”[1], puesto que la alternativa del estado era otra: arrasar con la mitad de los arbustos de coca de la región a fuerza de glifosato. El Padre Alcídes decía que lo mejor era “sembrar comida, dar salud y proporcionar desarrollo organizativo”[2]. Según la Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, en su ejercicio pastoral y organizativo, el padre Alcides trabajó sobre cinco “semillas” fundamentales para el “buen vivir” (sumak kawsay) comunitario: prevención de enfermedades; desarrollo de huertas; economía; participación y autonomía, y la política de participación comunitaria[3]. “¡El futuro de la vida humana es la autosuficiencia!”, pregonaba[4].

Insistió en la conservación de semillas nativas, el rechazo a los transgénicos, el fortalecimiento de producción agropecuaria, la promoción de la higiene y la transformación de los frutos del campo. Auspició la conformación de “cooperativas comunitarias” y “promotorías rurales” de personas que recorrían las veredas del territorio para verificar el avance de los proyectos de unidades sanitarias, el mejoramiento de cocinas, los cultivos y los procesos de transformación de frutas amazónicas en tortas, mermeladas, galletas y productos medicinales que se elaboran con hojas, tallos, raíces y frutos de plantas de la región, todas estas como rutas frente a los desmanes del monocultivo cocalero, el narcotráfico y la violencia.

Con el florecimiento de estos procesos se manifestó una necesidad en temas de comunicaciones. Por ello, y bajo el beneficio de una convocatoria del Gobierno Nacional, el padre Alcides impulsó el proyecto que luego sería conocido como “la emisora comunitaria Ocaina Estéreo”[5].

Los 14 años de sacerdocio y servicio a su pueblo quedan recogidos en una de sus locuciones: “No basta vivir en una comunidad para ser parte de ella, hay que sentir sus problemas y hacer activa en su solución”.

El 11 de septiembre de 1998, a mediodía, dos hombres con ponchos blancos entraron al templo de la parroquia Nuestra Señora del Carmen y acabaron con la vida del padre cuando oficiaba la eucaristía. Su cuerpo descansa bajo la sombra y el viento de un árbol de zapote junto al templo.

¿Qué hace la caminata evangélica de una persona así con nuestras vidas, con el territorio, con la fatalidad que a veces sostienen las cosas?

La conmemoración inició a las 10:00 am en el templo con el acompañamiento de varios sacerdotes del departamento del Putumayo, personal de la alcaldía, estudiantes y personas en general. Durante el encuentro, la hermana del Padre Alcídes, Olga, quien venía de la ciudad de Popayán, Cauca, compartió una pequeña reflexión:

Es increíble… aquellos que silenciaron tu voz iban a acabar con lo que habías construido, pero no contaban con que Alcides es gente, es su tierra, su cosecha y su voz; que aún se siente como hijo de Dios. Su voz no la callaron; se siente con mayor fuerza en el mismo suelo que pisó. Se equivocaron los que lo asesinaron porque el viento y los árboles pronuncian su nombre, y sus enseñanzas nos siguen acompañando.

En su homilía, alrededor del sermón de la llanura en el evangelio de Lucas, y desde ese mismo altar donde recibiera disparos Alcídes, el Padre Campo Elías de la Cruz habló de las acciones que se ven impulsadas por el amor. Señaló al Dios de la patria grande animándonos a la esperanza pues “con la utopía hay camino. Rememorar al padre Alcides es pensar en ese camino que, para él, más allá de la utopía, se sostiene con la gente”. Invitó a vivir una iglesia de rostro amazónico actualizando los legados del padre Alcides. En ese caminar, las bienaventuranzas no son ajenas a las realidades del territorio: acompañan al lamento donde los pobres alimentan las bienaventuranzas y se ubican como condición de la dicha y la gracia de la vida. Bajo ese gesto, el padre Alcídes fue capaz de decir a una mujer que lloraba: “Mujer, déjame llorar contigo”, haciendo vivo el dolor del otro, y viva la bienaventuranza.

El caminar con los pobres se hace uno con el dolor de la amazonía. No hay dolores departamentalizados. El dolor del pobre es el dolor de la tierra; el dolor de la tierra es el dolor del pobre, y el pobre es bienaventurado. No hay cuidado de la creación si no hay una vivencia honda de lo creado. ¿No es este un problema nuestro?, pregunta Campo. Mientras no nos duela, ¿qué le va a pasar a los pobres?

Nos desafió con más preguntas: “¿Qué nos dice el martirio del padre Alcides? ¿Hasta dónde su espíritu se mantiene? ¿Quiénes han cambiado el mensaje profundo por una caricatura?” Preguntaba estas cosas sabiendo que “los ricos ya han tenido su consuelo puesto que han tomado caminos más ‘livianos’”, y que, por el contrario, “quien ama al prójimo no acumula lo innecesario porque puede ser necesario al otro”.

Entonces brindó un ejemplo y alternativa pastoral de la propia comunidad que le escuchaba esa mañana:

Ustedes decidieron no sembrar coca y optaron por otras semillas. El día que nos falte la semilla moriríamos. El día que nos falte el agua moriríamos. En la amazonía está la presencia de Dios. Asumimos esas alternativas cuando abrazamos la tierra, la amazonía, “la fraternidad de las hojas” … Y mientras las multinacionales le van sacando la sangre al territorio es importante mirar con los ojos de Dios lo que le está pasando al mundo. Los ricos, las empresas, las compañías… tendrán dinero, pero no comida, no semilla. Es así como tenemos que creer con terquedad en el sueño de Jesús de Nazaret. Nuestro árbol más grande es creer, promover la armonía, la comida, la semilla. Vivir la eucaristía cósmica.

Al terminar la eucaristía, Edilberto me contó que un día de agosto de 2022, el padre Campo encontró en la parroquia un libro pequeño, desbaratado, de tapas verdes enredado entre pelusa y basura. Era una edición vieja del Himno del Universo de Teilhard de Chardin donde aparece un mensaje urgente:

La vida comunitaria en sintonía con el evangelio apuesta por la unión y la solidaridad de todas las criaturas que están consagradas en el Mundo, puesto que todas están suspendidas de un mismo centro real, una verdadera vida que experimentamos en común. Lo opuesto a esto es el empeño ciego de alimentarse de una única lectura de la realidad, un monodiscurso que requiere de los soportes de la violencia para sostenerse sobre un mundo al que destroza[6].

El padre Alcídes, en una eucaristía celebrada en los altares de la selva, decía a los campesinos:

Hoy Jesucristo llega a esta montaña como le gustaba a él y se mezcla con nosotros y camina aquí y nos reúne para que compartamos las yotas, la chicha, el guarapo, la amistad, unos dulces, un sancochito. Padre bueno, envía tu espíritu sobre esta misa que es la misa de la naturaleza y de nosotros[7].

Esta es la eucaristía cósmica sobre la tierra amazónica o saber decir Dios sobre el camino abierto y la tierra fresca.

Amén.

Alex and Xiomara’s appointments are made possible by your gifts to Disciples Mission Fund, Our Church’s Wider Mission, and your special gifts.

Make a gift that supports the work of Alex Maldonado-Lizardi and Xiomara Cintron-Garcia

[1] https://kaired.org.co/wp-content/uploads/Alcides-Jimenez-Chicangana.pdf

[2] Ibid.

[3] https://www.comisiondelaverdad.co/las-semillas-del-padre-alcides

[4] https://kaired.org.co/wp-content/uploads/Alcides-Jimenez-Chicangana.pdf

[5] Ibid.

[6] Tomado y adaptado del libro Incidencia del pensamiento Cósmico del jesuita y paleontólogo Teilhard de Chardin SJ (1881 – 1995) en el pensamiento Andino – Amazónico del Padre Alcides, de Ediberto Lasso Cárdenas, 11 de septiembre de 2023.

[7] Nota del periódico El Espectador citada por Ediberto Lasso.