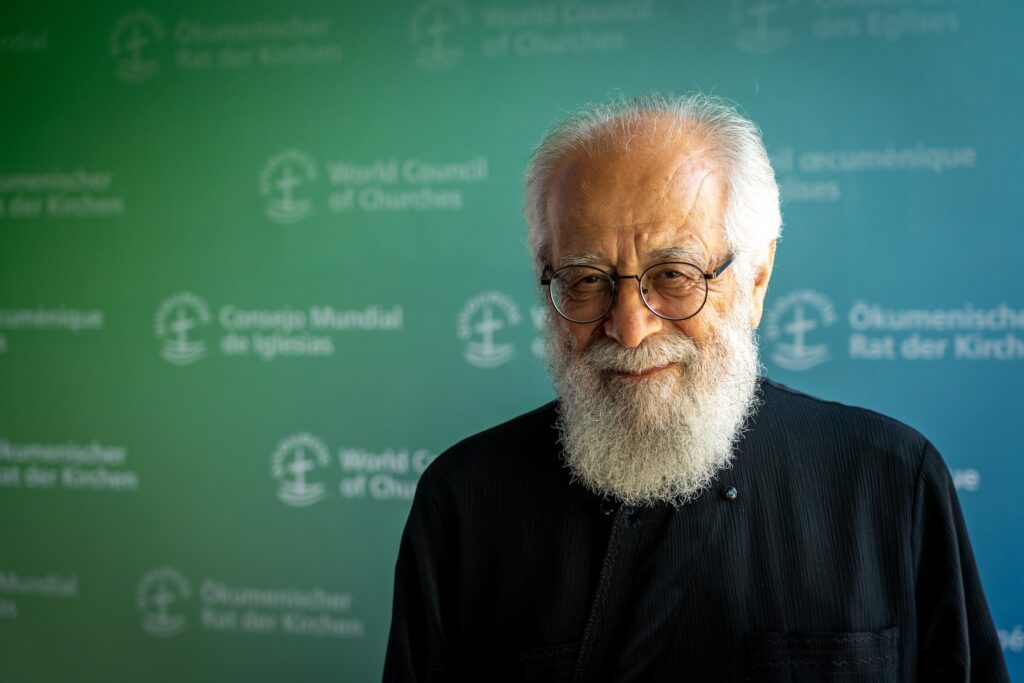

Metropolitan Dr Vasilios reflects on challenges—and hope—for real peace in Cyprus

The World Council of Churches (WCC) executive committee met in Cyprus from 21-26 November at the invitation of the Church of Cyprus, Holy Metropolis of Constantia and Ammochostos, extended by H.E. Metropolitan Dr Vasilios of Constantia – Ammochostos, Church of Cyprus, WCC president. The metropolitan reflected on the history of conflict and occupation, and the ongoing hope for peace, in Cyprus.

The gathering of the governing body, a significant encounter on the Pilgrimage of Justice, Reconciliation, and Unity, observed 50 years of Turkish occupation and division of the country and its impact on the people, churches, and the Republic of Cyprus.

It has been 50 years since the Turkish invasion of Cyprus led to the division of the island, the northern third inhabited by Turkish Cypriots and the southern two-thirds by Greek Cypriots, whose government is internationally recognized. The August 1974 ceasefire line became a United Nations buffer zone, along which Cyprus remains divided.

As Metropolitan Dr Vasilios recapped the history, he expressed the pain of a church that has been buffeted by the shifting winds of conflict and occupation.

“Actually the situation, to my point of view, of course, is becoming more and more difficult,” he said, noting that the people and the churches of Cyprus often feel subject to world leaders who wish to dominate the entire region.

“Cyprus, for Türkiye, is the ideal place for playing this role; you see in this in the areas in which they create military bases—they always increase,” he said. “Even if there were no Turks in Cyprus, Türkiye needs to have Cyprus strategically.”

With Cyprus strategically well-located between Europe and the Middle East—at least from a military perspective—the Church of Cyprus has endured, for hundreds of years, persecution, occupation, and lack of access to freedom of religion.

“In the Byzantine period, of course the most important event was from the fourth century when the Church of Cyprus became autocephalous,” the metropolitan said. “But for me, this was not just a church event—this was a political event, too.”

Eras of persecution

Then, during and after the period of the Crusades, the Church of Cyprus began to be oppressed and squeezed out of society.

“There was a decision to limit the Orthodox hierarchy from 14 or 15 bishops to only four, and the Orthodox bishops were not in the big cities but sent to the small villages, areas in which they were not able to have contact with the population,” said the metropolitan.

Later, there was a Latin hierarchy in Cyprus, so the Orthodox then were obliged to take part in official celebrations and processions of the Latin church.

“You had to accept the Pope as the head of your church,” said the metropolitan. “When a Cypriot went to the Holy Land, they were not accepted by the Orthodox to take communion because they were under the Latins.”

Metropolitan Dr Vasilios recalled a painful period of martyrdom for the Church of Cyprus in bygone eras: monks and bishops killed, and people barred from society.

The Ottoman Empire ruled Cyprus from 1571 to 1878. “But of course it was not an easy time, the Ottoman period,” said the metropolitan.

Even today, walking around Cyprus, one sees the influence of Latin and Venetian cultures.

“This is really very important, that they didn’t come to destroy but to build a culture, according to their western understanding,” said the metropolitan.

In the end—and somewhat ironically—the metropolitan reflected that the Latin kings of Cyprus may have in some ways been more favorable to the Orthodox than to the Latins themselves.

50 years of occupation

Türkiye invaded Cyprus on 20 July 1974—a day when the course of the nation’s history changed forever. The metropolitan himself lost five family members, including an uncle and cousins.

The Turkish invasion, following a brief Greek-inspired coup, caused massive destruction, with 6,000 soldiers and civilians killed (two percent of the male population in 1974). Still another 1,619 men and women, of whom 1,536 were Greek Cypriots and 83 Greeks, never returned home and were recorded as missing.

Metropolitan Dr Vasilios recalled visiting a small village after the invasion. “When I went to the village, I saw the village empty, and I shouted: ‘Is there anybody there?’ And an old man opened his door, and he said to me, ‘Everybody left. Nobody is here.’ The old people—they remained in their houses.”

Due to what happened in 1973, 142,000 Greek Cypriots and 55,000 Turkish Cypriots were displaced, and another 20,000 Greek Cypriots enclaved in the area were gradually forced to leave.

The UN has been involved in talks since 1999 to resolve an impasse between the two sides of the island.

Many people never returned, said Metropolitan Dr Vasilios. After living in Switzerland, he returned to Cyprus as a bishop.

“But it is very painful to see,” he said. “The feeling is that someone is saying to you: ‘it’s ours, and we give you the permission to come and celebrate.’ It’s not easy.”

Glimmers of hope

Metropolitan Dr Vasilios remains grateful for the support shown by the WCC, which includes visits from delegations and leadership, calls for prayer, statements from WCC governing bodies, and more.

He also believes that religious leaders must help create an environment that promotes the unity of Cypriots.

He observed that, after the collapse of the negotiations in 2017, there was time for reflection, from a political point of view, for both sides. He also acknowledged some attempts were made at a later stage with meetings of the leaders of the two communities, that developed some mutual confidence. Yet real engagement for negotiations remains elusive.

The metropolitan also sees Cyprus continue to be regarded as a strategic tool for military power. “The problem is that many countries saw and still see Türkiye as an important country for NATO, for economic interests like Germany, and for many, many other things, and so they keep silent—and yet they put sanctions to Russia for the invasion of Ukraine,” he said.

Also painful for the metropolitan has been the history of destruction of churches, monuments, mosques, and even cemeteries.

Over 500 churches in the occupied area are known to have been desecrated, along with holy icons, frescoes, and mosaics.

Following a United Nations agreement, there is a joint committee in Cyprus working to restore monuments of churches and Muslim mosques, cemeteries, and other monuments.

The metropolitan works to restore churches to save the Christian character of the area.

And, although the inaction is painful for the metropolitan to see, he also sees some glimmers of hope.

“Now, we see, for example a change of the policy of the United States,” he said. “We don’t know yet about Trump’s election but I suppose that the administration doesn’t depend on who is the president or not.”

One month ago, the president of Cyprus visited US president Joe Biden in the United States.

Metropolitan Dr Vasilios believes the inaction is due in part because the world sees people living peacefully in Cyprus—so they think peace is not urgent.

Yet Dr Metropolitan Vasilios has three-quarters of his diocese on the island of Cyprus under Turkish occupation—but no Christians are still living in the occupied part. “This has to be resolved,” he concluded.