Plant a tree

“What do you need for tomorrow?” Jorge, a quiet, attentive twelve year old asks me in Spanish, unsure of the words to formulate the question in a language so different from Tseltal Mayan, his mother tongue. I pantomime the items as I speak to make sure that he understands me. “Can you get a post hole digger, a bucket and a wheelbarrow full of compost?” He seems unsure of the word compost. “Will old leaves do?” and smiles when I nod and say “yes!”

Before breakfast, just as the sun burns off the fog, Jorge slogs through the mud to the church. I could hear the rain beating on the zinc roof of the sanctuary most of the night as I tried to sleep on make shift bed of wooden benches and an air-mattress. He motions for me to follow him down the path, and I welcome the opportunity for a walk. We reach his family’s adobe house and walk through his mother’s patio which is bursting with every color of flower imaginable. Pointing to the wheelbarrow full of composted leaves, a bucket with water and the pothole digger, he looks shyly at me waiting for affirmation. “This is exactly what we need!” I exclaim, backing up my words with a pat on his shoulder.

Before breakfast, just as the sun burns off the fog, Jorge slogs through the mud to the church. I could hear the rain beating on the zinc roof of the sanctuary most of the night as I tried to sleep on make shift bed of wooden benches and an air-mattress. He motions for me to follow him down the path, and I welcome the opportunity for a walk. We reach his family’s adobe house and walk through his mother’s patio which is bursting with every color of flower imaginable. Pointing to the wheelbarrow full of composted leaves, a bucket with water and the pothole digger, he looks shyly at me waiting for affirmation. “This is exactly what we need!” I exclaim, backing up my words with a pat on his shoulder.

After breakfast, a group of twenty or so children, ages 2 to 12, gather, wiggling and laughing in excitement. First, we play a memory game displaying different Chiapan trees. It doesn’t take long for them get the hang of matching trees to their descriptions and identify three or so that they have in their own community.

Next we play a composting game and again they are quick to figure out what items will biodegrade into compost and which will not. They understand that the seed of a tree can grow in the pile of leaves and vegetable peels but not in the pile of plastic.

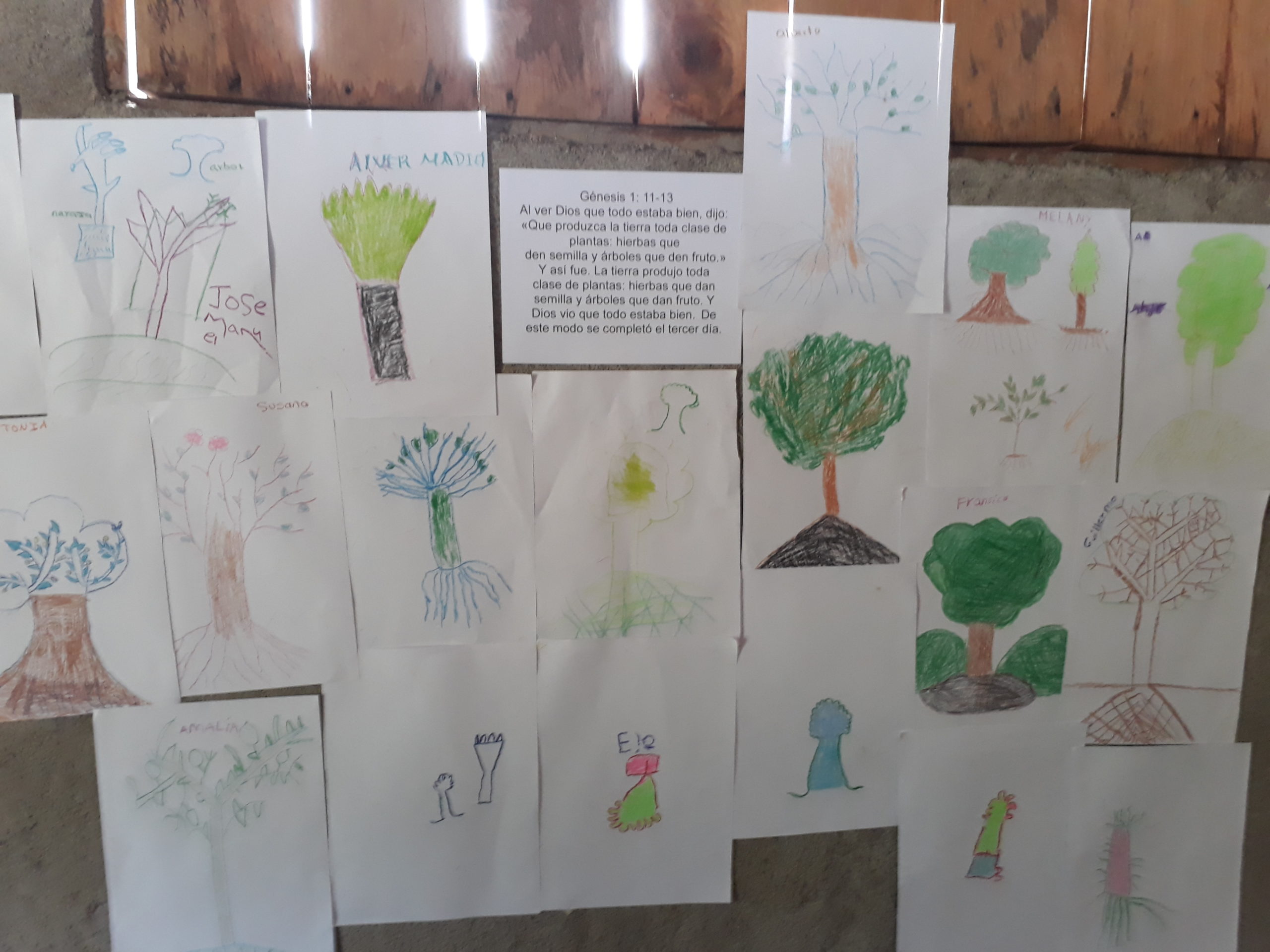

I show them the two native trees we are going to plant. Both are have medicinal properties and will grow to provide good branches for firewood. I ask them to draw how they imagine the trees will look if we take care of them. Soon we have a forest of drawings which we proudly display on the church wall.

I show them the two native trees we are going to plant. Both are have medicinal properties and will grow to provide good branches for firewood. I ask them to draw how they imagine the trees will look if we take care of them. Soon we have a forest of drawings which we proudly display on the church wall.

For the next part of the tree lesson, I pull out some play dough and ask them to shape all the things they can think of that either come from trees or depend on trees. Soon we have play-dough horses, who need the trees for shade and food, bird’s nests with eggs, snakes, bugs, books, pencils, shovels with wooden handles, and many other shapes appearing and disappearing as I try to learn their Tseltal names.

Finally, I show them how to plant the trees and protect them from the cows.. Then, with Jorge’s help, the children get to work. When the two trees have been planted with compost, watered and fenced, we choose names for the trees. One is “kuxlejal” which means “life” in Tseltal and the other is named “slamalil kinal” which mean “quiet place” but is also the expression for peace. We hold hands in a circle around both trees, and we pray a blessing over them that they might grow strong, full of life and provide a quiet place of peace.

Deforestation is one of many environmental challenges in the state of Chiapas, Mexico where Global Ministries partners with the Institute for Intercultural Studies and Research. As we drove into this village on the edge of the Lacandon Jungle, the largest rainforest in North America that still supports such wildlife as jaguars, caimans, tapirs, and a wide variety of other animals, reptiles, birds and insects, we can see large swaths of denuded mountainsides. When the trees are replaced by grazing cattle, the rains subside, the soils erode and the wildlife disappears. Timber companies, mining companies and ranches either convince or coerce local indigenous groups to sell their lands. Meanwhile, local communities fight for remaining patches of woods to claim the firewood and lumber they need for daily life.

Deforestation is one of many environmental challenges in the state of Chiapas, Mexico where Global Ministries partners with the Institute for Intercultural Studies and Research. As we drove into this village on the edge of the Lacandon Jungle, the largest rainforest in North America that still supports such wildlife as jaguars, caimans, tapirs, and a wide variety of other animals, reptiles, birds and insects, we can see large swaths of denuded mountainsides. When the trees are replaced by grazing cattle, the rains subside, the soils erode and the wildlife disappears. Timber companies, mining companies and ranches either convince or coerce local indigenous groups to sell their lands. Meanwhile, local communities fight for remaining patches of woods to claim the firewood and lumber they need for daily life.

The members of the church in this community have invited the staff of Institute for Intercultural Studies and Research to come and talk about starting a three pronged family food security project which could include tree planting, organic vegetable gardens, and raising small farm animals depending on interest and need. Even though the church will provide a meeting space, the project will be open to any family who is interested. We spend two days in the community getting to know the people. My task is to share with the women and children in three interactive workshops. In between the workshops, I help the older children and young women shuck corn and haul it in buckets to the local mill to make “nixtamal,” the soft dough used in making corn tortillas. There is nothing quite as delicious as handmade corn tortillas cooked on griddles over a wood fire! I play jump rope with the children. I laugh along with my teachers as I try to say words in Tseltal. I spend time sitting in the shade listening and smiling without understanding the conversations around me. Most of these women and children show up for the informational meeting and will be the ones who will work on the projects and reap the benefits.

The members of the church in this community have invited the staff of Institute for Intercultural Studies and Research to come and talk about starting a three pronged family food security project which could include tree planting, organic vegetable gardens, and raising small farm animals depending on interest and need. Even though the church will provide a meeting space, the project will be open to any family who is interested. We spend two days in the community getting to know the people. My task is to share with the women and children in three interactive workshops. In between the workshops, I help the older children and young women shuck corn and haul it in buckets to the local mill to make “nixtamal,” the soft dough used in making corn tortillas. There is nothing quite as delicious as handmade corn tortillas cooked on griddles over a wood fire! I play jump rope with the children. I laugh along with my teachers as I try to say words in Tseltal. I spend time sitting in the shade listening and smiling without understanding the conversations around me. Most of these women and children show up for the informational meeting and will be the ones who will work on the projects and reap the benefits.

I doubt the children or the women will remember much of what I said in my visit with them since we don´t speak the same language. I am convinced, however, that they will not forget what we did together: planting trees, playing games, making crafts, laughing, and getting to know one another. I hope that the two trees we planted will become tangible reminders that this project invites us to continue to learn from each other, care for the community and natural environment on which we all depend, and celebrate good “life” and “peace” with a blessing from the children.

I doubt the children or the women will remember much of what I said in my visit with them since we don´t speak the same language. I am convinced, however, that they will not forget what we did together: planting trees, playing games, making crafts, laughing, and getting to know one another. I hope that the two trees we planted will become tangible reminders that this project invites us to continue to learn from each other, care for the community and natural environment on which we all depend, and celebrate good “life” and “peace” with a blessing from the children.

Elena Huegel serves with the Intercultural Research and Studies Institute (INESIN) in Mexico. Her appointment is made possible by your gifts to Disciples Mission Fund, Our Church’s Wider Mission, and your special gifts.

Make a gift that supports the work of Elena Huegel